I would be surprised if I took a walk in Altoona and found someone that didn’t know something about the Battle of Gettysburg. Since the turning point battle of the Civil War is located a little over a two-hour drive from here, everyone seems to know something and some are very knowledgeable. I first visited Gettysburg when I was 12 and gave my first tour to friends at 18. I have been there so many times for both vacations and educational seminars that I have lost count. I spent the summer there in 2000 at Gettysburg College’s Civil War Institute on the Abraham Lincoln scholarship. It's a place everyone should visit. This year is the 160th anniversary of the three-day battle that changed the course of the Civil War.

In June of 1863, the Army of Northern Virginia turned north from the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia and marched toward Pennsylvania. The story of what happened when they reached Gettysburg is well documented and not the focus of this column. As they marched north, the Union Army of the Potomac pursued them on their eastern flank to block them from turning for an assault on Washington, D.C. Lincoln was always fearful of a Confederate attack on Washington, so while the capital of the U.S. was defended, panic ensued in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania’s capital. In a time before satellite and airplane reconnaissance, military intelligence was a slow process that relied on in-person visual observation typically done by cavalry or individual scouts and delivered in person. General Lee’s second invasion of the north set off alarms throughout western Pennsylvania, including Blair County and Altoona, since Lee’s ultimate destination was unknown.

Blair County was a potential target for several reasons. First, the railroad shops of the Pennsylvania Railroad were located in Altoona. Confederate forces were destroying portions of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad on their march north. The role of railroads in moving supplies and men had been critically important since the first battle of Bull Run when rebel forces arrived by train and saved the day for the Confederates. Second, Altoona had been the host of a northern Governor’s Conference in 1862, a significant event where the northern governors voted to continue supporting Lincoln and the war effort despite Union losses and increasing costs. While the governors were long gone, burning the town would have been a psychological victory. Another reason was the fact southern Blair County, known locally as the Cove, was the site of many iron furnaces—furnaces that produced some of the best iron in the country. That iron was formed into large chunks called “blooms” that were then shipped to Pittsburgh where it was used to make the famous Rodman guns. Rodman guns were massive artillery with a 15-inch bore and were big enough for a man to climb inside. Finally, the coal mines in southern Huntingdon County serviced by the East Broad Top Railroad provided more than 250,000 tons of coal yearly for the war effort, and that railroad added to the target rich environment of its neighbor, Blair County. Blair County needed help, and this is the mostly forgotten story of the brave local volunteers who quickly assembled, like the Minutemen of the Revolutionary War, to defend Altoona and Blair County.

The story begins on June 13, 1863, when Union forces under the command of General Robert Milroy in Winchester, Virginia, came under attack from Confederate forces marching north. Winchester was a hot spot of the war, changing hands dozens of times, and by June 15, the rebels held Winchester, and what was left of Milroy’s outnumbered forces were in a disorganized retreat. Some of his troops went to Harper’s Ferry while others fled to Pennsylvania where they regrouped at Bloody Run, Pennsylvania (Everett). Some went another 48 miles and stopped in Altoona. The advancing Southern force wreaked havoc on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad before continuing north in pursuit.

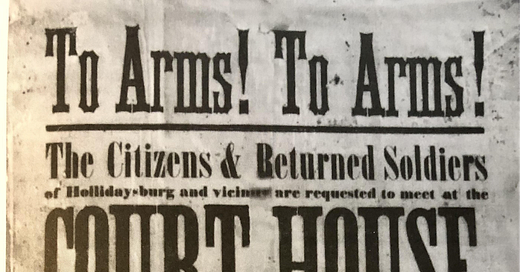

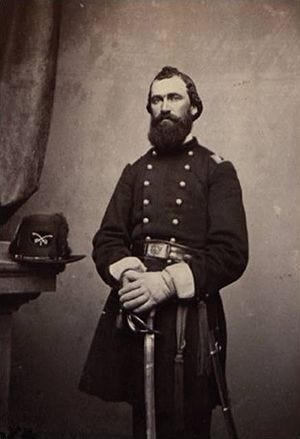

Governor Andrew Curtin of Pennsylvania, knowing the route to central Pennsylvania was now open, called for volunteers to defend against the invasion. A letter from Curtin arrived for Jacob Higgins, a native of Williamsburg then residing in Duncansville, to take command of all Blair County forces in Hollidaysburg and to organize a defense. Higgins had served in the Mexican-American War and was wounded in the assault on Mexico City. Colonel Higgins had just returned from his nine-month enlistment where he commanded the 125th Pennsylvania who fought in the Antietam and Chancellorsville campaigns. The 125th at Antietam is renowned for its repeated courageous attacks in the West Woods behind the Dunker Church where their monument stands today. General Darius Couch of the Susquehanna Department of the Union Army requested Higgins raise a regiment of emergency volunteer militia (approximately 1,000 men). Higgins announced in his recruitment “Let your ranks be full and come prepared to support the dignity and preserve the peace of the County of Blair.”

That task would prove to be both easy and challenging. On one hand, it was easy to convince farmers, railroad workers, miners, iron workers and craftsmen to defend their homes. Some, like Higgins, had already served, and Higgins called on experienced officers to assist with recruiting and command. Men like Colonel Jacob Szink of Altoona—who also served at Antietam with the 125th, where he had his horse shot from under him—stepped up for the emergency militia. Szink led the recruiting effort in Altoona where, as a foreman of the PRR blacksmith shop, he knew many men. Others had little to no experience but mustered the courage to leave their homes and volunteer. It was no easy task to face General Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and its record of victories, including its most recent thrashing of the Union Army at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Quickly organizing men with no training, many of whom carried their own hunting rifles and rode their own horses, would be difficult.

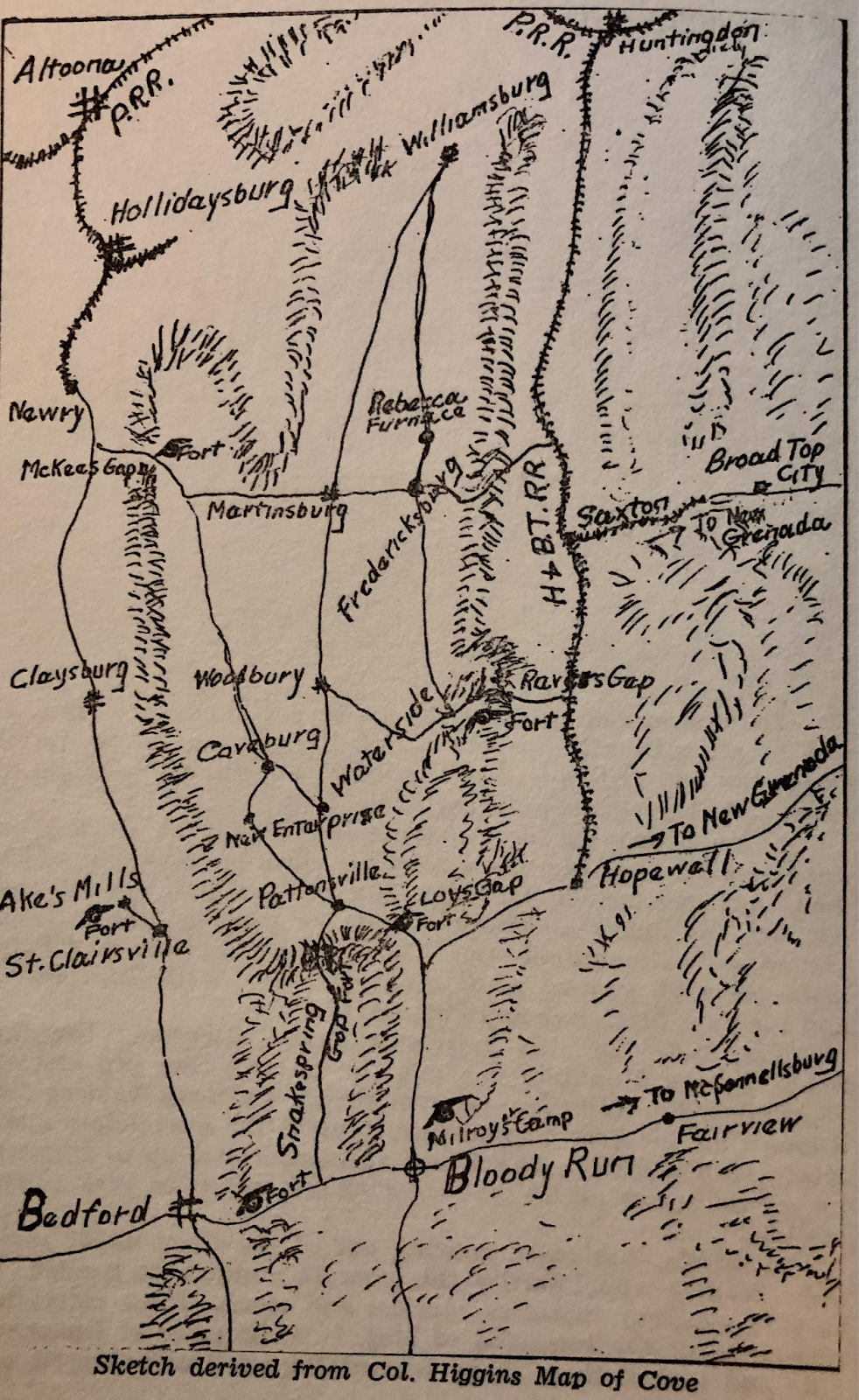

A supply train arrived in Altoona with guns and ammunition and was sent on to the positions Higgins designated for fortification. The railroad line ran to Hopewell, and then the supplies were taken by wagon to Buckstown (St. Clairsville today). The primary task would be to quickly assemble fortifications in the form of trenches and breastworks. Men got to work gathering stones and cutting trees. There were four gaps to be fortified in the mountains of southern Blair County extending into northern Bedford County: McKee’s Gap south of Newry with a route leading directly to Hollidaysburg and Altoona, Pattonsville Gap (Loy’s Gap) southeast of Pattonsville (Loysburg today), Snake Spring Gap located south of Woodbury coming from Bedford, and Raver’s Gap that was east of Woodbury and a direct route to Martinsburg and Rebecca Furnace. The high ground at St. Clairsville (near Osterburg) was also fortified where Szink’s force of men from Altoona and the Cove were encamped.

The urgency to finish the defenses was hastened when word was received that Confederate Cavalry under the command of General John Imboden, part of Jeb Stuart's command and the advanced guard of Lee’s western flank, were headed toward Blair County. Reports indicated he was marching on Altoona to burn the railroad shops. More men arrived from the Cove area of the county with picks, axes and shovels to continue the construction of fortifications. As the fortifications went up, so did the level of anxiety and fear in the county.

On June 17, Higgins extended a picket line to Bloody Run (Everett) in the south. Word arrived at his command that the Confederates had occupied Chambersburg to the East, and the panic that gripped Blair County now also permeated Harrisburg. More supplies arrived by rail in both Huntingdon and Altoona as volunteers continued to arrive at the fortified encampments. The number of volunteers was more than 1,000 with one official count numbering 1,387. It was hard to acquire an actual number as some men would come and go from camp. Since they were close to home, some would go home to check on the farm and return, while others would go home for a good meal and then return. Contingents from Hollidaysburg numbered nearly 250 men and 40 were from Altoona. Other volunteers came from every region of Blair County, including Duncansville (38), Newry (50), East Freedom (100), Tyrone (73) and Logan Township (79). There was also a company of African-American volunteers. An additional 500 men arrived from Johnstown and Cambria County, answering the governor’s call. It should be noted the population of Blair County at the time was 28,000, but large numbers of men were already serving in the war and were away from home. Many of the volunteers were those previously considered too old or unfit to serve.

Elements of Milroy’s retreating forces from Winchester decided to make a stand and set up at Bloody Run (Everett) on June 18. These men were from the 12th Pennsylvania and the 1st New York, both cavalry units. Later, remnants of other units would arrive. Colonel Jacob Szink, under orders from Colonel Higgins, arrived at Bloody Run from St. Clairsville (Buckstown) with his contingent of volunteers. Szink’s men from Altoona were to move to Cove Mountain and construct fortifications. Later they joined forces with Milroy’s regulars and coordinated to move east toward McConnellsburg. Rebel forces continued to scout the area for open routes and to obtain (steal) fresh horses. The fear of losing one’s horse(s) was considerable for the residents of Central Pennsylvania since they were essential to their financial well-being. Milroy’s men with Szink’s volunteers prepared to set out toward McConnellsburg to engage the invaders. Higgins received a cannon, an accompanying cassion and 30 crates of ammunition by train from Philadelphia on June 20. He turned it over to Milroy’s command.

After days of fluctuating numbers of men in the camps, Higgins established strict rules for his volunteers to put an end to the men coming and going at their own discretion by requiring passes for all entering and leaving camp. The number of emergency militia now surpassed 2,000 and those not preparing to advance on McConnellsburg continued to work on the fortifications. Today, the entrenchments at Snake Spring near Martinsburg can still be seen despite being somewhat overgrown with vegetation. Higgins forces were estimated at 2,500 at their peak during this crisis. A large number of militia were stationed near Ake’s Mill (near Osterburg) along the Altoona-Claysburg-Bedford road as a reactionary force that could respond quickly to approaching threats.

By June 22, word had spread that fighting was expected to begin any day. Bells ringing to sound the alarm, albeit a false alarm, seemed to ring daily in Blair County communities. Confederate scouts had reported that the passages through the Tuscarora Mountain at Cove Mountain in southern Blair County were blocked by Higgins’ men. The Confederates decided they would dispatch 2,500 infantry supported by artillery and 300 cavalry troops to expel them. At this point, Szink, whose men were in an exposed position on Cove Mountain, decided to withdraw to avoid being outflanked and overwhelmed by the approaching larger rebel army. Two days later, 25 volunteer scouts set out under the order of Captain William Wallace toward Fort Littleton to determine the location of the Confederate force and their intentions. In quick order, the rebels were spotted, and Lieutenant McDonald quickly rode to Wallace to inform him, announcing, “They’re a comin’ Captain! And there’s a hell of a lot of them!” The small force wasn't prepared to engage the confederates, but they had no choice; McDonald ordered his men into position and to open fire into the Confederate force. Wallace soon arrived with reinforcements and poured fire into the rebel cavalry, causing them to fall back in disorganization. The Confederates didn’t realize they faced a smaller force and halted to bring up artillery. This action, without any serious casualties to either side, stalled the larger Confederate brigade for hours until cannon fire forced a Union withdrawal. This delay allowed Szink to properly retire from his exposed position. The Confederates captured McConnellsburg, but disaster to Szink’s men, now numbering 150, was averted.

Central Pennsylvania was still in peril as Confederate Cavalry under General Imboden continued as a threat, and more under General Albert Jenkins were on the move followed by the infantry of Rodes Division, part of Lee’s main force. On June 26, Robert E. Lee entered Chambersburg and set up headquarters to guide the attacks on Central Pennsylvania with potential targets ranging from Harrisburg to Altoona. An easy route to Harrisburg was denied to the rebels when 750 militia from the Harrisburg region, after attempting to hold a bridge at Columbia over the Susquehanna River, burned the bridge to prevent its capture and use by Lee’s army. Three days after Lee’s arrival in Chambersburg, two events would change the course of this campaign. First, the expedition of men from Bloody Run made its way to McConnellsburg and attacked the cavalry forces of Imboden (18th Virginia Cavalry). Troopers from the 1st New York under the command of Captain Abram Jones along with Szink’s volunteers flanked the Confederates and drove them back, halting Imboden’s plan to advance and sparing Blair County from attack. Saber fighting, uncommon in the Civil War with the technological advances in rifles, was reported. Two Confederates were killed and approximately 30 were captured. These were the first two Confederate deaths in Lee’s Pennsylvania campaign. The second event on June 29 was that Lee had received word from a scout named H.T. Harrison that the Union Army of the Potomac had broken camp and was indeed moving north. Lee was at first surprised that he wasn't made aware of this by Jeb Stuart’s Cavalry command, but they were off conducting raids, failing to provide essential reconnaissance. Nonetheless, Lee quickly sent word to his three Corps commanders to head west as quickly as possible to meet the Union Army at the crossroads of Gettysburg where he hoped to bring an end to the war by defeating the Union Army and marching on Washington. Imboden’s forces turned to the east. As we know, the battle didn't turn out the way that Lee hoped.

Meanwhile, back in Blair County, tensions began to subside as citizens waited anxiously for news from Gettysburg. On July 3, the culminating day of the battle that witnessed the infamous Pickett’s Charge, unusual atmospheric conditions created a strange phenomenon that allowed folks as far away as Pittsburgh to hear the artillery duel that day. Imboden and his cavalry arrived in Gettysburg that same day and set up to protect the western flank of Lee’s soon to be retreating forces. News arrived in bits and pieces in Blair County, but eventually word was received that Lee’s forces were in full retreat. The Blair County volunteer emergency militia, who were given the name the “Chicken Raiders,” returned to their homes, families and jobs. The fear had abated and was replaced with the pride of local men who on short notice answered the call. Many, including Higgins, would serve again in the regular Union forces before the war ended.

If you would like to see some of the defensive positions, the best place is along SR1005 (old PA 36) about five miles south of Loysburg where trenches can be observed. There is a state historic marker along the side of the road with a small place to pull off. The entrenchments are visible on both sides of the road, and you can imagine how Higgins envisioned this position blocking the Confederate approach. On the opposite side of the road from the state marker, there is a state game lands gravel road that leads to an Eagle Scout project with a turnaround, gravel path and a sign. It's about 50 yards on the gravel road to the sign and more trenches to explore.

It's easy to look back and understand why the “Chicken Raiders” story is an all but forgotten chapter of history. The Battle of Gettysburg became a turning point of the war. Lee would never again be on the offensive, and the staggering losses at Gettysburg were never fully replaced. It is the most well-known battle of the war, and Gettysburg Military Park has more than two million visitors annually. Numerous books, movies and documentaries cover the multitude of fascinating stories that are directly related to the battle. Blair County was spared a direct attack by Confederates; the closest they came were Confederate pickets within eight miles of Martinsburg.

There are many “what if” scenarios, and one could ask, “What would have happened had the Union Army been delayed entering Pennsylvania?” It is likely the Confederates would have pressed on north to Harrisburg as well as west to the target rich communities of Blair County. It's improbable the emergency militia could have stopped a full Confederate frontal assault, but they discouraged a smaller one by fortifying those gaps. Fortunately, no “Altoona Ablaze!” headlines were necessary. The result of a large-scale battle here will thankfully never be known, but what we do know is brave volunteers from Altoona, Hollidaysburg and other communities in the area left the safety of their homes to face a much stronger, better trained and better supplied army to defend their homes, families, neighbors and country. Yes, even better supplied. The volunteer men from Blair County were called the Chicken Raiders because they lacked supplies and were often looking for food … including chickens from area farms, thus the name “Chicken Raiders”. This challenge, one of many, further reminds us that these men and their service deserve to be remembered.

Sources:

From Winchester to Bloody Run by Steven Hollingshead and Jeffrey Whetstone

Minute Men of Pennsylvania by Milton V. Burgess

GPS Coordinates for PA Roadside Marker and Trenches

N40.1009, W78.38953

Jim, An excellent article and an appropriate tribute to Blair County's role in The Gettysburg Campaign ! Your research was considerable and you combined it into accurate and understandable article. You are still teaching but now your class room is much larger. Thank you for keeping the area history alive. Sincerely, Bob Resig

Great tribute to the brave people from our region. I thoroughly enjoyed the detailed accounting of the role of the "Chicken Raiders".