Sometimes I started class with a mystery artifact or a mystery word. A word that was likely to be unknown to my students. A word that might evoke quizzical looks and the occasional “huh!?!” A word like “bissextile.” In full disclosure, I didn't even know this word until I was doing a fact check on a detail for this column. That's when I discovered “Bissextile Day” and “Bissextile Year” are the technical names for what is more commonly known as Leap Year and Leap Day, and their story is nearly 3,000 years old.

The first calendar was created in 753 B.C. by Romulus. It only had 10 months and 304 days, plus an undefined winter period. It was eventually modified to include 12 months with a total of 354 days and no fluctuating winter period. Since the actual time for the earth to orbit the sun is 365.224 days, it did not take long before the seasons were out of place. Harvest was celebrated before crops were planted. The remedy was to add leap month. If leap day can be confusing, imagine an entire extra month.

In 45 B.C., Julius Caesar decided to end the practice of inserting leap months to correct the calendar by issuing a new calendar. That calendar is the basis of the calendar we use today. The Julian Calendar, as it became known, set the calendar year at 365 days, much closer to earth's orbit time. Since it wasn't perfect, an extra day was inserted every three years, thus creating a leap year. It is called a leap year because normally if a given day such as your birthday falls on a Tuesday one year, it would be Wednesday the next year, but when the extra day is added, there is a leap of one day so that it falls on Thursday.

By the 16th century, the calendar was off by approximately 10 days, which impacted the proper and timely celebration of Easter. Pope Gregory XIII issued a new calendar to correct the problem. The new calendar, known eponymously as the Gregorian Calendar, was implemented at first only in countries that practiced Roman Catholicism. The first action was to fix the 10 days the calendar was behind by creating a one-time leap night. When people went to sleep on October 4, 1582, they woke up the next day and it was October 15, 1582: ten days later. After this correction was made, the long-term plan was started to add an extra day once every four years to keep the calendar accurate. This new calendar also added a special rule to keep everything aligned: Skipping leap year is to happen in years that are divisible by 100 and not divisible by 400. As a result, leap year was skipped in 1700, 1800, 1900 and will next be skipped in 2100. I hope you have all of that—a test follows the last paragraph.

As convoluted as it sounds, it worked—except that Protestant countries in Western Europe and Orthodox countries in Eastern Europe didn't want to take directives from the Pope, so they refused to follow the new calendar. Other parts of the world had their own calendars too. Eventually, the Gregorian calendar was adopted by other European countries. The British, and subsequently the American colonies, adopted it in 1752. It did require some adjustments. George Washington, for example, was born under the Julian calendar on February 11, but we now celebrate his birthday on February 22 on the Gregorian calendar.

Are you wondering what happens if you are a “leapling”? This is the moniker for someone born on February 29. You celebrate your birth on February 28 or March 1 in non-leap years as you wish. Legally, it is listed on the birth certificate as February 29, but activities with age requirements like buying a lottery ticket, obtaining a driver's license or joining the armed forces become March 1 in non-leap years.

Sometimes legal issues arise from leap years, such as an inmate sentenced to a year of incarceration unfairly having an extra day in a leap year. In an actual case where this happened, the court decided a year was exactly 365 days.

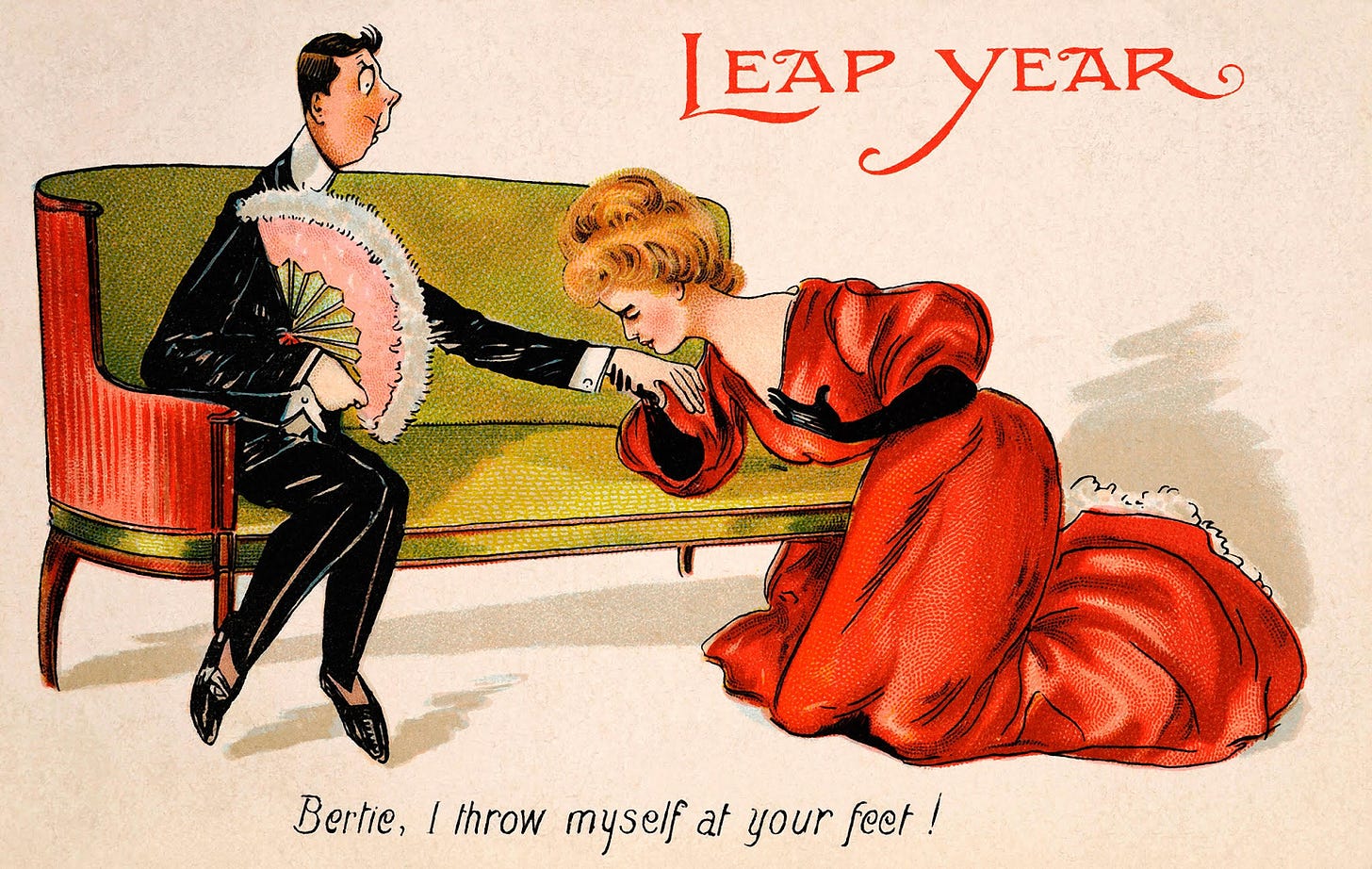

An old tradition no longer practiced was that February 29 was the one day of the year that women could propose to men. Women were reminded by relationship guides—publications that are an interesting record of bygone eras—to do so in a private moment, to explain why the time was right for marriage and to emphasize in her proposal all that she loved about the man. It was suggested she buy him a watch and not a ring. If the man said no, as a punishment/apology, he must buy her twelve pairs of gloves—gloves for her to hide her embarrassment of not having an engagement ring. This tradition eventually shifted “the gift of denial” to a dress and then to a fur coat. If he did say yes, further advice was, ironically, not to set the day of the wedding for February 29—that's bad luck.

You likely now know more than you ever wanted to know about leap year, so we can forgo the aforementioned warning of a test. As always, thanks for reading!

This was excellent! I learned some new things, like where the term “leap” actually comes from.

The only thing I would add is why we began with a 354 day calendar. Earlier calendars back to the time of the Mayans were lunar, and not Solar. Since the Moon’s period is exactly 29.5 days, it was easy: you just alternated 29- and 30-day months. But that required those early cultures to add a 13th month every 3 years to maintain pace with the Sun, which is where your article led off.

Nicely done!

Absolutely fascinating, Jim. I knew none of this. Reading your columns is like taking a mini-college course! Thanks for the enlightenment!